Interview and review by the Yorkshire Post Newspaper.

Charging into Hisotry

Anthony Dawson, a Yorkshire-born archaeologist and historian, has

spent more than a thousand hours of painstaking research collecting

these letters and poring over the Victorian newspapers that originally

published them. They form the basis of his new book – Letters from the

Light Brigade: The British Cavalry in the Crimean War – which describe

in detail what it was like to fight in the battles of Alma and Inkerman,

the siege of Sebastopol, as well as the charge of the Light Brigade.

Many

of the letters were written by Yorkshiremen to their families and

friends and were published in local papers like the Leeds Mercury. They

include graphic accounts of the fighting, of the terrible loss of men

and horses shot and they describe, too, the miserable conditions with

men dying as much from disease as from their wounds.

Thursday, 21 August 2014

Tuesday, 12 August 2014

Attack on the Bilboquet and Gringolet

Many cavalry theorists of the 1840s and 1850s considered that the days of cavalry, especially armoured heavy cavalry, were numbered. The 'Beau ideal' for many, including British observers, were the French 'Chasseurs d'Afrique' who were trained as both light cavalry and as mounted infantry. Rifled muskets which had an effective range of 800-1000 metres meant the end of brightly coloured uniforms and were deadly against tightly-formed ranks of cavalry. Despite the assertions of Captain Louis Edward Nolan (1818-1854) in England, the Crimean War (1853-1856) showed that cavalry could not overcome well-formed infantry and that the cavalry charge was more deadly to it's own army than to the enemy. Often considered to have out-performed her Ally, the French cavalry came unstuck when attempting to attack two Russian artillery batteries during May 1855.

Monday, 28 July 2014

1854 - The Railways Go to War

Whilst, quite rightly, the role of the Railways in this the centenary of the outbreak of the Great War and 75 years from the outbreak of World War 2, has been stressed as the unsung hero of both conflicts, it is 160 years since the Railway went to War.

In March 1854 the unlikely alliance of Britain and France declared war on Russia, starting what was to later be known as the Crimean War. Often described as the first 'modern, inudstrial' war, the Crimean War saw the first mass use of the railways to move troops and materiel but also in the warzone itself.

In the build up to hositilities in the Crimea, men, horses and supplies were moved by rail. When the Scots Greys - a cavalry regiment - marched from their barracks in Nottinghim to Liverpool (via Manchester) the men and horses went by foot, but their baggage was sent by rail, via Chesterfield, Matlock, and Buxton. When the 7th (Royal Fusiliers) Regiment of Foot left its barracks in Mancehster, it did so in ten trains chartered from the LNWR, 150 men per train. Some 3,000 tons of forrage from horses was despatched from Leeds by rail before being put on board ship and sent out to the warzone.

One of the most audacious plans for the railways involved sending the entire British cavalry force (the 'Heavy' and 'Light' Brigades, totalling around 2,000 horses) all the way accross France using the newly opened PLM (Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée) railway. Over 100 wagons and specially-contructed horse-boxes were collected in Calais for this monumental task. The backers of this scheme positted that sending the cavalry by rail was quicker than sending them by sea to Marseilles, safer and would prevent the horses from 'dropping off in condition'. Sadly, it was cancelled at the last minute due to protests from communes in the South of France who, with memories stretching back 40 years), did not want to see British troops marching through their villages.

The failure of the British supply system (Commissariat) became a national scandal which brought down the Coalition Government of Lord Aberdeen in the new year of 1855. In order to remedy the crisis at the front, Messrs. Peto & Brassey of London - the famous railway contractors - volunteered to build a railway in the war zone and at their own cost! It became known as the 'Grand Crimean Central Railway.'

Initially worked by horses and stationary engines on incline planes, the line was relaid with heavier rails and the more severe inclines avoided so that steam locomotives could be used.

The first steam locomotive to go to war was the 'Alliance'. 'Alliance' was an 0-6-0 tank engine, built in Leeds by E. B. Wilson & Co. and had been volunteered by Sir John Lister Kaye who used her on his colliery railway near Wakefield (now the National Coal Mining Museum). Alliance was re-fitted in Leeds, fitted with armour plate and 'Her iron sides adorned with the English,

French Turkish and Sardinian flags conspicuously painted thereon.'

She was soon joined by a sister engine, 'Victory', in September 1855 after the fall of Sebastopol. A further three locomotives were sent out: two from the LWNR and the fith, called 'Swan' from the St Helens' Railway.

After peace was declared on 30 March 1856, the railway was sold piecemeal at auction.

After peace was declared on 30 March 1856, the railway was sold piecemeal at auction.

Friday, 25 July 2014

The Battle of Kanghil

From the Souvenirs of Lieutenant-Colonel le Vicomte de Bernis, 6th Dragoons

"The

29th September, the general d’Allonville has three columns in

movement. They left Eupatoria at three o’clock in the morning. The first,

directed to the south-east, towards the Lake Sasik, by the sea was to take

position by Sak. There, they met a few Russian squadrons, but they were easily

dealt with by the fire from two gunboats. The second column, commanded by

Muchir Pacha, advanced towards Doltchak which they ruined during their passage

to deny provisions to the enemy. The general d’Allonville is at the head of the

third column, composed of twelve squadrons from his division, and the horse

artillery battery of captain Armand. Two hundred Bachi-Bazouks preceded them;

and attached were six Egyptian battalions. They marched for Chidan by way of

Doltchak, where they would rendezvous with the two other columns, and they were

reunited around ten o’clock in the morning. They

had before them and had to shoot at enemy squadrons that

were successively calling up their reserves. There were eighteen squadrons

of Uhlans, several Cossack

squadrons and artillery. They

maneuvered by withdrawing and seemed to be

prepared to turn our right,

to come between the lake and us.

Tuesday, 22 July 2014

Captain Nolan

The enigmatic Captain Nolan

Captain Louis Edward Nolan was one of the most famous

cavalry officers of his day, having served in - and trained by - the Austrian Army and with the

British army in India. His two books on cavalry were forthright and forward

thinking, but yet – probably thanks to Tony Richardson’s 1968 film ‘Charge of

the Light Brigade’ - he is depicted as hot-headed villain of the piece; indeed

Mark Adkin (‘The Charge’) has gone so far as to suggest that the Charge of the

Light Brigade was the deliberate act of Nolan. So who was Captain Nolan?

Monday, 26 May 2014

Letters from the Light Brigade

Published 30 June 2014, price £25.00

On the 25th of October the enemy advanced, and stormed our advanced positions on some hills, which were well fortified, and unfortunately occupied by the Turks, but the rascals fled before the Russians came within 150 yards of the forts; our artillery came up, and the Russians recovered the guns, where we were exposed to shot and shell for upwards of two hours, but the positions were lost, we slowly retired a short distance. The Russians advanced direct on to us, on the ground of our camp. Our heavy dragoons were ordered to charge them and they fled, although their numbers were sufficient to overwhelm our handful of cavalry. At this time, the Light Brigade formed up on the left, on some ground which commanded a long valley about two miles long, at the end of which the enemy retired. By some misunderstanding, we were ordered to advance and charge the guns, which they had formed up full in our front at the extreme end, and here took place a scene which is unparalleled in history. We had scarcely advanced a few yards, before they opened on us with grape, shot and shell. It was a perfect level, the ground only enough for the 17th and 13th to advance, the rest of the brigade following. To our astonishment, they had erected batteries on each side of the hills, which commanded the whole valley; consequently, a dreadful cross-fire opened on us from both sides and in front, but it was too late to do anything but advance, which we did in a style truly wonderful, every man feeling certainly that we must be annihilated. Still we continued on, reached the very guns, charged them, took them; but, there being no support, we were obliged to retire, almost being cut up. Out of our regiment, we assembled only ten men mounted, and one or two officers… I escaped – thank God! – without a scratch; but my poor horse got shot through the head and in the hind quarters, and a lance was through my shoe bag. It was a most unwise and mad act. One thing, there is no blame attached to the Earl of Cardigan, for he was ordered to do it, and he did it most noble. We charged up to the very mouth of the guns, and since then the 17th and ourselves have scarcely been able to make one squadron between us. The 4th Light Dragoons are nearly as bad. The Earl is very cut up contemplating it, and points it out to the officers as the effect of charging batteries. The daring of the thing astounded and frightened the enemy. (Letter from a Sergeant of the 13th Light Dragoons to his parents in Stockport Stockport Advertiser (1 December 1854), p. 4.)

Presented

here for the first time in 160 years are letters home from the men of the

British Cavalry involved in the Crimean War, the culmination of thousands of hours of research by Crimean War historian, Anthony Dawson.

There

will be a Book Launch at the historic Westgate Chapel (Unitarian) on 2nd

July at 7.30 – which will also include wine, nibbles and a display of Crimean

War artefacts. Admission is free.

Thursday, 6 February 2014

Was there a battle plan for the Alma?

The answer, undoubtedly is yes.

The overwhelming body of evidence from French sources, from Le Marechal Saint-Arnaud down to a Capitaine of Infantry, suggests that indeed there was a battle plan for the Alma, a plan which, according to Le General Bosquet, would have been effectively a re-play of Austerlitz.

The Plan.

The traditional English language historiography of the Alma, which originates with the report of W H Russell ot The Times and Kinglake's vitriolic defence of Raglan suggests that the Allies fought their own separate battle, which was, of course, won by the English despite the French. But this is not true.Saturday, 25 January 2014

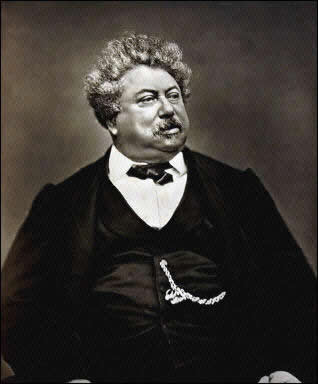

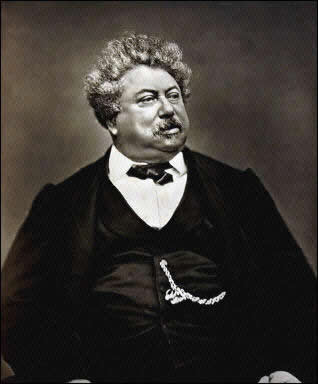

The Author and the Zouave

Le Capitaine Richard records the following 'Curious Incident' which took place the Barracks of New France (Caserne de Nouvelle-France) where the Officers of the Zouaves de la Garde had their mess.

"The Capitaine Adjutant Major Petit, who conversed with Alexandre Dumas, one day whilst walking in a boulevard, invited him to dinner, with no ceremony. Dumas accepted. The Captain shortly spoke to the Colonel Lacretelle to warn of the coming of the illsutrrious novelist and also to warn all officers. But the band was playing that evening, taking its turn of duty, at the dinner of the the Emperor. However, a reception without music is a wedding without violins, so the Adjutant-Major went to the Tuileries to change the tour of duty of the band of the Zouaves. But it was impossible! It is too late, musicians from other regiments were already scattered out of their barracks en route to the various theaters of the capital, where they almost invariable played in the orchestras.

"The Capitaine Adjutant Major Petit, who conversed with Alexandre Dumas, one day whilst walking in a boulevard, invited him to dinner, with no ceremony. Dumas accepted. The Captain shortly spoke to the Colonel Lacretelle to warn of the coming of the illsutrrious novelist and also to warn all officers. But the band was playing that evening, taking its turn of duty, at the dinner of the the Emperor. However, a reception without music is a wedding without violins, so the Adjutant-Major went to the Tuileries to change the tour of duty of the band of the Zouaves. But it was impossible! It is too late, musicians from other regiments were already scattered out of their barracks en route to the various theaters of the capital, where they almost invariable played in the orchestras.

In the Mess

Inspired by his visits to the Mess of the British Household Troops at Windsor, le Colonel Fleury introduced the British-style 'Mess' first to the Regiment des Guides, and then to the Imperial Guard. The introduction of the Mess sytem to the Imperial Guard fostered - as it did in Britain - a tight bond between the Officers and a far greater Esprit de Corps than in the Line. Officers of the Guard were also encouraged to behave as 'gentlement' and were therefore allowed to marry: something considered undesirable for an officer of the Line. The Officers of the Guard were to set an example of 'Good conduct' to the rest of the Army. The Mess system and privileges such as being allowed to marry were intended to be aspirational. In reality, the Guard cut itself off from the Line, thinking itself better, jealously guarded its privileges leading to the Line harbouring resentment toward it.

Marcel de Baillehache, who enlisted as a volunteer in the Lanciers de la Garde left a striking impression of the mess in his memoires.

"The Colonel Beville invited us to Dinner at Saint-Germaine where the Officers had the mess, situated in the Avenue de Boulingrin, in a very beautiful brick and stone house in the style of Louis XIII... one noticed a large 'N' carved in the stone above the door. ...

This Mess of the Guard was very superior , and the service left nothing to be desired. The servants were very numerable, in the most part men from the Regiment, wearing a sky blue livery with gold buttons and, on the day of a Grand Reception or a Gala, wore short white breeches, white stockings and buckled shoes. At the time to eat, a servant would stand by the doors and the Maitre d'Hotel, dressed all in black, would advance in front of them an announce 'Le Colonel et ces messieurs a service.'"

Friday, 24 January 2014

Palace Duty

Marcel de Baillache records the daily routine and spectacle of the Guard Mounting at the Tuileries Palace:

The differant detachments of the Infantry and Cavalry for the Service Battalions and Squadrons at the Chateau are also placed under the command of a Superior Officer of the Guard, who was senior to the Colonel, Commandant du Chateau, and usually a General Aide de Camp to the Emperor on Duty.

The Troops departed from their quarters for the Courtyard of the Tuileries before eleven o'clock in the morning. When the Guard was mounted at the Ecole-Militaire, there arrived one of the Ecuries of the Emperor, situated on the Quai d'Orsay, a dozen charming small ponies mounted by grooms wearing a green livery. They formed a rank in the Courtyard facing the band. These horses, destined for the young Prince [Imperiale] for which their training was complete, so that they were prepared for military noises of all kinds.

When this little column arrives at the Gate of the Cavalry [Grille de la Cavalerie] which leads onto the Avenue de la Motte-Pquet, nothing was as graceful as these small horses so pretty and so montes, following the last row of music and accompanied by a gentle movement of the head one of those catchy quick-steps composed by the excellent bandmaster of the 2e Voltigeurs, Sellenick.

The Cavalry were followed by the Infantry, directed towards the Pont Royal, which they had to cross to enter the Chateau by the small gate called L'Empereur.

When the Sapeurs with their white aprons, often with the cross of honour and other commemorative medals attached, arrived at one of the Guard Houses by the wicket gate, the Guard shouted out "Halt! Who goes there?" And the column would stop. The Drummers and Music would stop playing. The Corporal Sapeur beats on the gate.

A Corporal and two men came out of the Sentry Houses and moved in front of the sentries and presented arms. The Corporal repeated"Who goes there?" To which was responded "France!" ; "Which Regiment?". The Corporal-Sapeur replied again "Imperial Guard, 1st Regiment of Grenadiers!" The Corporal on Sentry answered "Go as you please."

The troops resume their march; the drums begin to beat ; the trumpets bray, fifes and music play; the troops file into the Courtyard procded by their superb Tambour-Major... The troops form En Bataille in face of the Chateau, the Cavalry on the left of the Infantry.

As eleven o'clock is rung from the clock in the ancient Clock Tower [Pavillon d'Horloge], the drums beat Aux Champs, and the Officer of the Guard enters from the Tower, ordering the troops to Present Arms. The sentries at the Pavillion repeat these movements. The Eagle is carried forward, its silk is nearly entirely black, and torn by Russian and Austrian bullets. The drummers sound Au Drapeau...

The Eagle is placed in the centre of the Line, and the Colonel commanding the Chateau and the General Commanding the Guard passes through the ranks on inspection.

The Guard then marches past and after this last movement, is detailed off to provide the Sentries who occupy the differant posts of the Chateau. The Eagle of the Regiment is furnishsed with a Guard and is laid upon two fascines of muskets facing the Guard House which is opposite the Pavillon d'Horloge.

Messieurs les Officiers

The French army of the Nineteenth Century is generally considered to have been egalitarian/meritocratic in nature. Indeed, the motto of the French Republic is "Liberte; Egalite; Fraternite". But even after 1789 the French officer class was as class-ridden as ever.

Wednesday, 15 January 2014

Voltigeurs, Camp de Chalons, 1857

"The Skirmish"

"Tending to the wounded"

"At rest" (the Officer appears to be wearing a Line officer's Tunique but with the aiguilette of the Guard; he also has an epee).

More on the Voltigeurs from Capitaine Richard

"In the night of 21 to 22 May, the Russians had erected a very

important gabionade 60 metres from the wall of the cemetery, in front of

our Attacks on the Left. General Pelissier, who was by then Commander

in Chief of the Army of the East, was resolved to capture these works to

get rid of this dangerous work.

Three columns of attack were organised for this operation. The Right-hand Column under the orders of General de La Motterouge was formed from the elite companies of the 1st Regiment of the Foreign Legion, supported by battalions of the 28th and 18th Regiments of the Line. They had, for the reserve, the greater part of the 1st Regiment of the Voltigeurs of the Guard. This column debouched on the south-east corner of the cemetery to attack the Russians lodged on the slope of the ridge which dominated everything from the north.

Three columns of attack were organised for this operation. The Right-hand Column under the orders of General de La Motterouge was formed from the elite companies of the 1st Regiment of the Foreign Legion, supported by battalions of the 28th and 18th Regiments of the Line. They had, for the reserve, the greater part of the 1st Regiment of the Voltigeurs of the Guard. This column debouched on the south-east corner of the cemetery to attack the Russians lodged on the slope of the ridge which dominated everything from the north.

"Voltigeurs of the Garde... earned for themselves a name worthy to be classed with the Old Garde of Napoleon I"

Attaques des Ouvrages du 22e Mai

General

Canrobert was replaced as French General-in-Chief by General Pelissier on 19th

May 1855, and he brought with him a new energy to the French army. Whilst the ordinary French soldier

believed Canrobert had been the right man at the right time during the winter

of 1854-1855 (Pelissier was known not to care what the causality list was so

long as the job got done), the morale of the French army had plummeted in spring

1855 when the campaign season had not opened with a grand attack. Despite this,

Canrobert remained highly popular with the troops, so much so that in Summer

1855 Pelissier packed him off back to France following the disaster of 18th

June the blame for which most French soldiers put on Pelissier claiming that

Canrobert would never have ordered such an attack.

La Bapteme de Feu

The 1st Expeditionary Brigade of the Imperial Guard landed in the Crimea between January and April 1855; the final elements sailed from Marseilles on 23rd March, landing at Kamiesch 19th May, via the Camp de Maslak, near Constantinople.

L'Affaire du 1e Mai

The Russians had constructed two redoubts and rifle pits on the French left, controlling the approaches to the Bastion du Mat (Flagstaff Bastion) and Bastion Central (Central Bastion), causing the French approaches to Sebastopol to stall. As one anonymous Officer of the Voltigeurs wrote: The dominant position of the place d’armes would soon [be] completely neutralised, and we would be able to put [in] good order, all our work leading to siege on the left. It was necessary to remove it at any price.A soldier's life is terrible hard...

Rudyard Kipling famously quipped " A Soldier's life is terrible hard" - especially so for a Cavalry Trooper. Not only had to look after himself and his own equipment, but his horse and horse tack were his number one priority: only after his loyal mount had been fed, watered and cared for could he attend to his own feeding and watering. Presented here is the daily routine for the Royal North British Dragoons, c.1830

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)