The Intendance Militaire

handled the French army’s commissariat from 1817. It was the civil

administration branch of the French army, and as well as feeding and clothing

the army, it was responsible for providing the medical service (Service de

Santé Militaire), veterinary services (Corps

de Veterinaires), military justice (Justice Militaire), and moving

the army’s baggage and rations (via the Train des Équipages).[1] British observers were invariably full of

praise for the Intendance, not only for its organisation but also its

apparent efficiency in providing shelter, food and transport for the army;

French soldiers were thought ‘not to want for anything’.[2]

The perceived superiority of the French Intendance became important

because of the press-campaign by W. H. Russell et al, and letters home

from the front, which exposed apparent failures of the British commissariat,

compared with the French, during the Siege of Sebastopol. The perceived

failures of the British system led John Roebuck MP to call for a Parliamentary

Inquiry into the management of the campaign, which ultimately led to the fall

of Lord Aberdeen’s Government in January 1855.

Wednesday, 15 February 2012

Intendance Militaire

Was the Intendance as realyl as bad as many post-1870 commentators suggest? or was it a victim of circumstance?

Tuesday, 7 February 2012

I am coming to the conclusion

that the British unstinting praise of the French army in the Crimea and

Baltic was due to yes the British Army being broken-down, BUT

importantly to the Army Reformers and increasingly vocal and dominant

professional and middle classes, the British Army was unredeamably

broken because of its Aristocratic nature. The French army appealed to

the professional classes because it promoted based on merit; French

officers were promoted from the ranks and that fulfilled themiddle class

emotional and moral ideal of the 'self made man'. Furthermore, that the

Army was seen as being Aristocratic meant that many of the perceptions

of the aristocracy went hand in hand with that perception: the Army was

therefore, lazy,"jobbish" and not "professional", it was not run my "men

of business" or "practical, experienced men" whereas the French army

was egalitarian, promoted on merit and its army had that "Practical

experience" It was rather ironic, therefore that it was the least aristocratic parts of the army, - the Commissariat nad Medical Services

- who were condemned as being failures and evidence of miss-management

and the most aristrocratic part of the French army - the Etat Major (Staff Corps)-

was singled out for praise for being not the reserve of an elite. The

French Commissariat (Intendance Militaire) fulfilled many middle class ideals of

centralisation, but was perhaps centralisation taken too far, as it has

subsumed the medical services, train, veterinaries in fact all the

non-combat and support roles into one monstrous organisation that was

qausi-military (civilians in uniform) which was as full of the

"jobbing", "favouritsim" and other faults levelled at the British

army. The French Commissariat was resented by Line officers especially since it undermined the authority of Regimetnal Staff Officers and that Line officers had to salute Comissariat staff despite them being civilians.

Rerfom organisations such as the effervescent Administrative Reform Association which counted Dickens and Thackery as members, believed that the Government should be organised on the same lines as big business and that "Public Management should be brought up to the same level as Private Management". MPs, government bureaucrats and army officers should be the "Right Man in the Right Job" - the "Right Man" being a well educated, experienced, middle class professional. The desire for the army to be run like big business and on "practical lines" resulted in philanhtopric men such as Joseph Paxton creating the Army Work Corps to build barracks and huts in the Crimea, largely recruited from Navvies who had built his 'Crystal Palace' or the putting out to tender to Peto & Brassey for the construction of a railway to carry supplies for the army rather than the military. Bursting mortars in Baltic, leaking boots and unfulfilled private tenders, however, broke the spell that middle class businessmen and practices could solve all the problems of the British army.

Rerfom organisations such as the effervescent Administrative Reform Association which counted Dickens and Thackery as members, believed that the Government should be organised on the same lines as big business and that "Public Management should be brought up to the same level as Private Management". MPs, government bureaucrats and army officers should be the "Right Man in the Right Job" - the "Right Man" being a well educated, experienced, middle class professional. The desire for the army to be run like big business and on "practical lines" resulted in philanhtopric men such as Joseph Paxton creating the Army Work Corps to build barracks and huts in the Crimea, largely recruited from Navvies who had built his 'Crystal Palace' or the putting out to tender to Peto & Brassey for the construction of a railway to carry supplies for the army rather than the military. Bursting mortars in Baltic, leaking boots and unfulfilled private tenders, however, broke the spell that middle class businessmen and practices could solve all the problems of the British army.

Sunday, 5 February 2012

The Zouaves at the Malakoff

General

Lebrun’s account of the capture of the Malakoff by the French.

General

Barthelmy Lebrun was the Chef d’Etat Major (Chief of Staff) to General – later

Marechal – Patrice MacMahon. He recounts in his letters how the capture of the Malakoff was far from easy and could have ended in a serious disaster for the French due to the scaling ladders, planks and gabions intended to cross the ditch being late and too few in number.

Contextual thoughts: Significance of the French Army and British Army Reforms

The French Army and British Army reform.

The

French army had long been viewed by the reform-minded elements of the British

army as being superior and the means to measure the supposed inefficiency of

the British army. The French army was considered professional compared to the

‘amateurishness’ of the British.[1]

The British army was viewed at home with ‘frustrated indifference’, especially

compared to the Navy, and the ‘belief in the incompetence of the British army

died hard’.[2]

The British army had notably failed in America (1776-1781) and in the Low

Countries (1794-1795), but saw considerable reform under the Duke of York as

Commander-in-Chief, the fruits of which were felt as early as 1801 with victory

in Egypt, the British army entering what was termed by the anglophile Baron

Antoine-Henri Jomini as ‘l’époque de sa régénération’ (the period of its

renewal).[3]

This may also be attributable to the ‘degradation’ of the French army and navy

during the Revolution rather than any ‘regeneration’ of the British army.[4]

The overall, effect, however, was an upsurge in the morale of the British army

and how the government and society perceived it. In the period 1815-1854 the

British army was gradually becoming more reconciled with the country at large,

especially with growing territorial ties for recruitment and the publication of

the first regimental histories in 1836.[5]

The army, however, was still viewed with deep suspicion by radical and

conservative politicians alike which slowed or prevented reform: the former

championed by Richard Cobden and John Bright of the ‘Manchester School’,

arguing for army reduction on the grounds of economy, but more importantly,

because of a deep-seated mistrust of a standing army. This distrust was also

the key argument used by the conservatives for a small army with a divided

command and maintaining the status quo. The only impetus for army reform was

recurrent Imperial disputes and war-hysteria in Europe.[6]

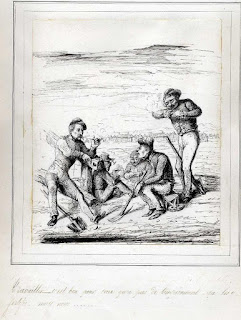

Cantinieres

Cantinières, or female canteen keepers, were a unique feature of the

French army, and the American historian Thomas Cardoza has described the Second

Empire (1852-1870) as their “Golden Age”.[1]

It was the period in which the cantinière, like the Zouaves,

caught the imagination of the French and European public alike – their pretty

uniforms coupled with implied good looks as well as an almost saintly

disposition led them to appear in numerous contemporary printed material, notably

cheap prints and pamphlets.[2]

This chapter will study the cantinières thematically, understanding

their popular perception through media such as the theatre and commercial

images. Comparisons between the

treatment and role of women in the British and French armies will be discussed

as will the relationship between the cantinières and British soldiers.

Finally, the French view of the cantinières, as well as the respect

these women engendered on the battlefield will be examined.

Military Thought

British Military Thought

The British army in the period 1815-1854 is

traditionally viewed as being stagnant in thought and reform, perhaps best

being summed up by General Sir George Brown’s resignation over the introduction

of a new drill manual in the 1830s. Whilst Hew Strachan has challenged this

view,[1]

suggesting that the British army had a lively internal debate over reform and

modernisation, Peter Burroughs has suggested that even though reform did take

place, the army was perhaps more conservative than Strachan suggests.[2]

This chapter will examine the origins of military thought in the British army

leading up to the Crimean War and also the army’s perception of the French, its

traditional and chief European rival. Origins of the domestic understanding of

the French army will also be discussed as well as military thought in the

French army.

Unitarians and the Crimean War.

The Crimean War, fought from 1854-1856 between an

alliance of France, Great Britain, Piedmont and Turkey against Russia was the

result of a “churchwardens squabble” over who should control the keys to the

Holy Places in Jerusalem and Bethlehem. The French, on behalf of the Catholic

Church, had had control over them since the Crusades, but following the French

Revolution had rather lost their religiosity leaving a space for Russia on the

behalf of the Orthodox Church to step-in. Thus when Napoleon III re-asserted

his ancient right to protect the Holy Places and to place a silver star bearing

the French coat of arms over the supposed site of the Manger of Christ in

Bethlehem, an international incident was in the offing. In France and Russia,

therefore, the Crimean War was viewed as a Crusade to rescue the Holy Places

from heretics; to the Turks the Crimean War was a fight for survival: they had

recently suffered a crushing defeat to the Russians in the 1820s and the

Ottoman Empire was in the process of falling apart. Indeed Turkey had

reluctantly gone to war with Russia to avoid an Islamic revolution at home, so

great was the pressure from hard-line Moslem clerics and students and their

call for a Jihad (Holy War) against Russia.

In Britain, the Crimean War had all of the religious overtones it did to

her allies; Protestant Britain was standing up to the ‘bully’ of the Tsar and

the un-reformed Orthodox Church. The leitmotif of the war was ‘the Crusade of

civilisation against barbarism’ and religious liberty. Thus it is rather ironic

that in Britain the ‘crusade of civilisation’ and religious liberty resulted in

the persecution of religious minorities, such as Unitarians – a religious

position only legal in Britain since 1813.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)